How can we turn waiting into a bit of wonder?

In urban life, mundane moments, such as waiting at traffic lights, are often overlooked. For this university research project during my time at Bauhaus University Weimar, we asked, What if waiting became a moment of play?

Our answer: RhymeTime, a playful, interactive music box designed for pedestrian crossings. It invites people to sing, rhyme, hum, or interact with it, aiming to turn everyday crossings into mini-performances: a public intervention that is part safety, part poetry, and part fun.

Our design was grounded in five principles of playfulness (Guitard et al., 2005): creativity, curiosity, humour, pleasure, and spontaneity. We also honoured a core idea: play should be open and intentional, never forced.

We probed what makes people engage at crossings, how play, control, and sensory feedback affect behaviour, and where design and distraction meet. Through engaging in literature research, case study analysis, and expert interviews, we found that pedestrians craved a sense of control, even if it was as simple as pressing a button. With inhibitions lowered to facilitate cross-use of familiar, playful elements like music, we learned that interventions like these must respect the environment and its inhabitants, focusing on people with special mobility needs and those who are visually impaired.

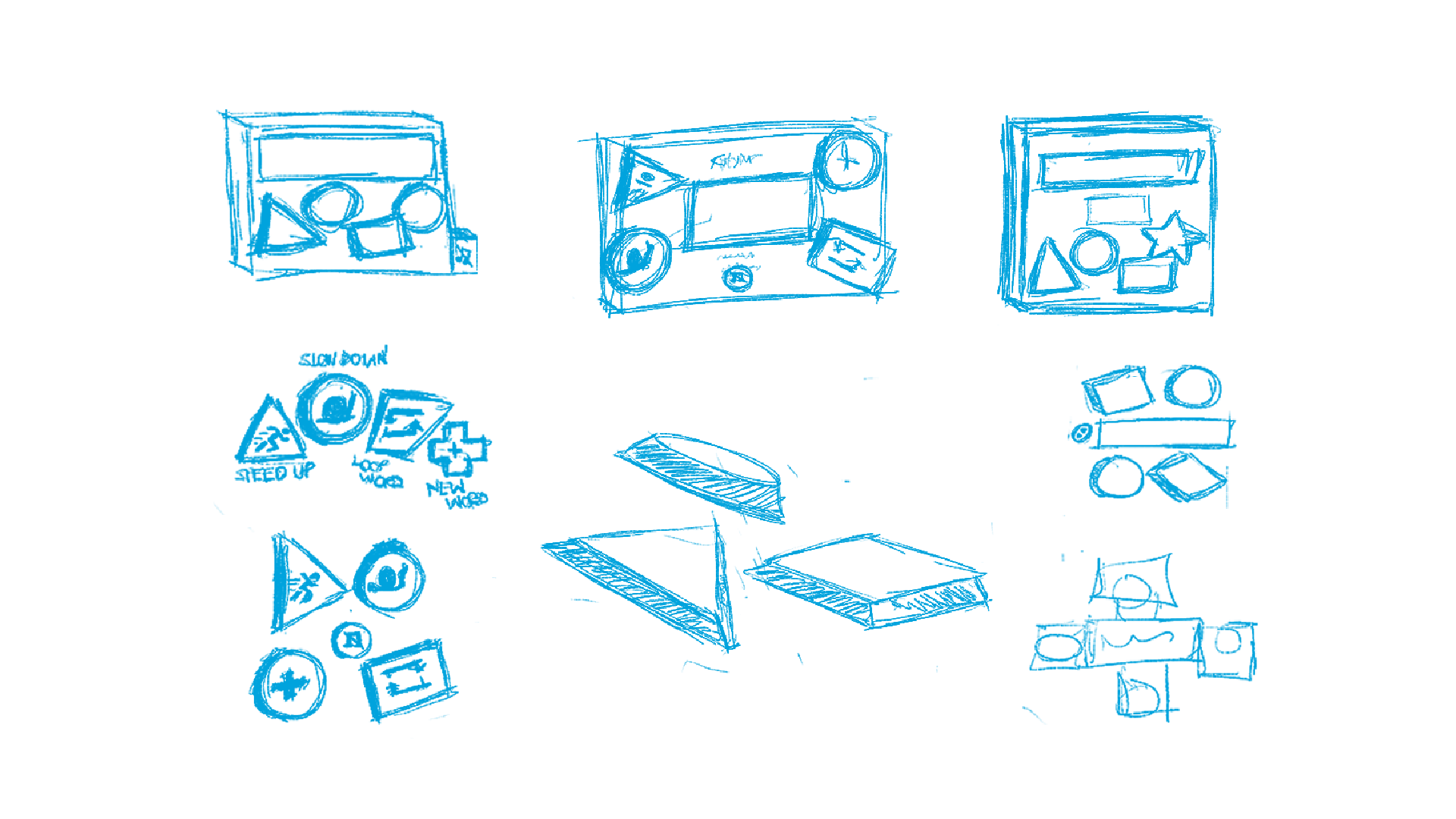

Before landing on this concept, our ideation process used body storming as a form of role-playing scenarios at street crossings. We explored concepts such as interactive foot patterns, music boxes with call-and-response features, and rhyming games that are activated during red lights, bringing us closer to the idea of Rhyme Time.

Prototyping RhymeTime

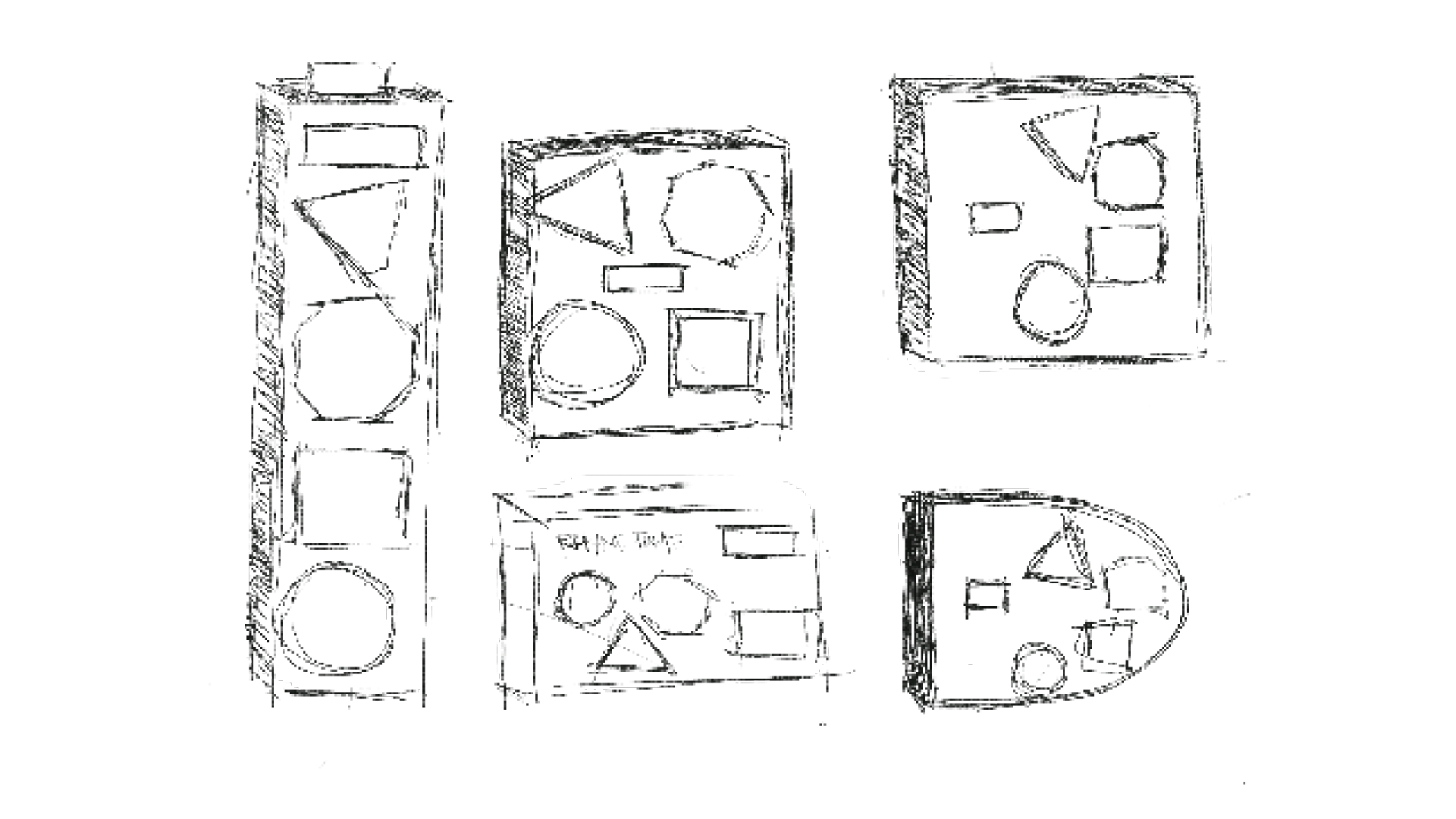

Initial sketches imagined a simple box with musical prompts. Tasks like "rhyme," "sing," or "hum" aimed to spark joy rather than perfection or expertise. Here, we began questioning what would incentivise pedestrians to engage with the device, disregarding feelings of shyness or embarrassment.

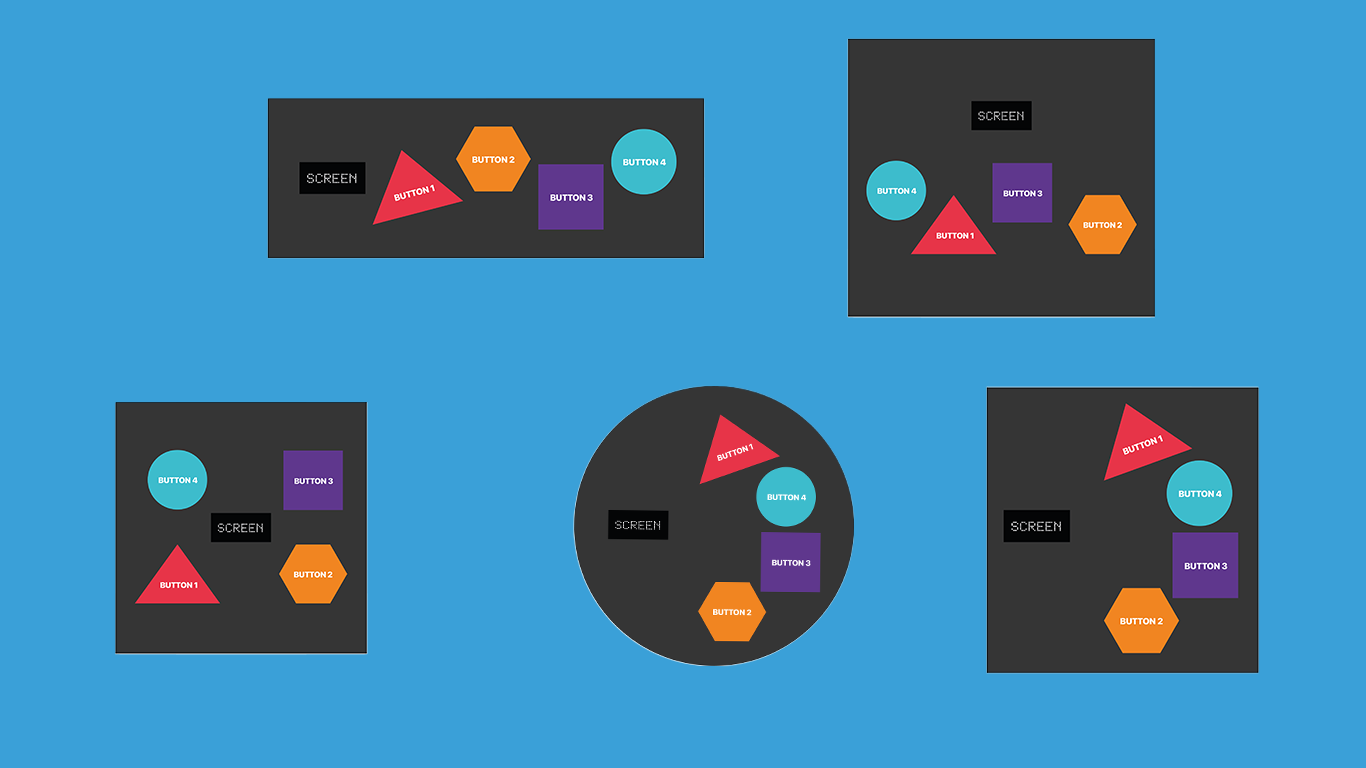

The prototype evolved into a Bristol-board box with colourful geometric buttons, each triggering tempo changes, tracks or prompts. Inside, we used Adafruit hardware to simulate interaction for testing.

Due to hardware limitations, we created a video mockup for user testing and exhibition.

Interaction and Experience

We focused on creating a low cognitive load and high delight experience. Introductory sounds and applause sounds provided feedback, giving pedestrians small wins for engagement and holding them at bay, lowering the intentions of jaywalking.

Physical Form

Geometric buttons offered a tactile variation of interaction: Circles slowed the tempo of the music, triangles sped it up, and squares changed the track or prompt.

The final form was boxy but friendly, with soft buttons for interaction, distinguished from the start button, which was hard and easily integrated into the pedestrian landscape.

Music and Sounds

Music choices were upbeat, simple, and familiar, licensed royalty-free tracks with adjustable BPM (beats per minute). An important decision is to give users control while keeping the interaction light and accessible.

Validation

Due to the prototype stage and duration of the project, we validated our approach through expert interviews to gain insights into the design and potential.

Cognitive Psychologist: Primarily applauded the sense of control but warned of distraction, notably for children and impaired pedestrians.

Musician: Suggested familiar, low-effort prompts like "yodel" or "hum" to reduce performance/competence anxiety that can arise from "sing" or "rhyme”.

Traffic Engineer: Supported playful interventions to reduce "dead-time," but raised concerns about audio conflicts for not only visually impaired users but also polluting residential areas. They recommended a start button and limiting installations city-wide.

Results and Reflection

There are several successes to report from this exploration of playfulness in urban spaces, notably the prototype's effective introduction of play into a non-play setting, with experts agreeing that the system could reduce jaywalking and enhance the urban experience.

The concept successfully embodied all five dimensions of play without overwhelming the users; however, the device has a lot of room for improvement, such as adding enhanced visual cues to support sound and testing and refining how users interact with the device (e.g., opting in via the suggested start button) to mitigate noise fatigue. And finally, addressing safety concerns, particularly in high-traffic zones, is especially important for children.

The concept successfully embodied all five dimensions of play without overwhelming the users; however, the device has a lot of room for improvement, such as adding enhanced visual cues to support sound and testing and refining how users interact with the device (e.g., opting in via the suggested start button) to mitigate noise fatigue. And finally, addressing safety concerns, particularly in high-traffic zones, is especially important for children.

Looking back on this assignment and this course, 'Let's Have Fun: Exlploring Playfulness in Interaction Design' instilled a core principle in my design career: the integration of playfulness in design to create delightful user experiences.

It easily became a reminder that even small design choices can shape how people move, wait and connect. We can design for joy without losing sight of responsibility. In the end, it asked a simple question: Why don't cities feel more human and engaging?